Bonds, Interest Rates & The Inverted Yield Curve

Posted on 8/4/2022

Priavte Wealth

Overview:

With inflation heating up and interest rates on the rise, fixed income investments are critical barometers for global markets. Yet fixed interest investing is particularly complex. In this Insights article we unravel the fundamentals of fixed interest investing, and the effects that interest rates have on markets.

Let’s start with some basics

‘Fixed interest’ broadly refers to investments that pay the investor fixed interest payments (coupons) until an agreed maturity date. At maturity, investors are repaid the principal amount they invested.

Government bonds are a good example of fixed interest investing. Governments issue bonds to raise capital for planned spending. Depending on the timeframe for spending that capital, a government may issue short term bonds (1 – 3 years) or longer-term bonds (10 years +).

The risk-free rate

Government bond yields are used as a benchmark for ‘risk-free’ returns against which investors can assess required returns from all asset classes, including equities. If all you can get is 1% p.a. from a 10-year Australian Government bond, then you might be inclined to take more risk and buy shares in companies with steady dividends or strong growth potential.

Through most of 2020, that’s exactly what you could get from a 10-year Aussie bond. And despite the concern around COVID-19, the share market recovered quickly from the covid-induced lows as defensive alternatives offered little in return.

Then as markets began to look towards a post-COVID world, bond yields started to rise, anticipating eventual interest rate increases and stronger economic activity. By November 2021, the 10-year Aussie bond had reached almost 2%.

Unfortunately for bond investors, when bond yields go up, the capital value goes down. If you hold a bond paying 1% interest and the market starts to price the fair value for that bond to be 2%, then your bond becomes less attractive… why would someone buy your 1% bond when they could buy a new one paying 2%? Consequently, the capital value of your 1% bond is marked down.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, bond yields have spiked up more because oil prices jumped and consequent supply chain issues caused inflation expectations to rip higher. The Aussie 10-year bond yield now sits a tad above 2.8% and US 10-year treasuries just over 2.4%, after trading as low as 0.5% in 2020.

The yield curve

Market commentators often use the term ‘yield curve’. This is particularly important when analysing market expectations about possible central bank rate rises to control inflation.

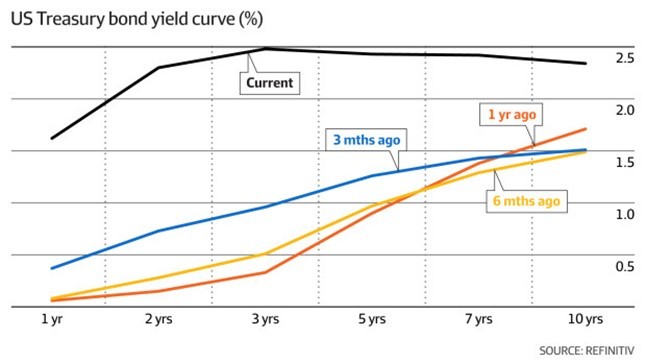

The yield curve is the relationship between the rates on short maturity (1 year, 3 year) and long maturity (10 year) bonds. The yield curve usually slopes up as bond investors demand higher yields on their money to compensate having to wait longer for repayment, as well as needing an acceptable return margin above anticipated inflation.

The short maturity end of the bond market is closely tied to central bank policy. As central banks raise rates, the short-end yield tends to rise with them. Recently we’ve seen the yield curve flatten with market expectations for central bank rate hikes.

Central bankers have a tough job. Many current inflationary pressures are due to things out of their control, such as the rise in oil prices because of the war in Ukraine and the supply chain disruptions brought about through covid lockdowns and the war in Ukraine. Central banks can’t control any of that with higher interest rates, except to push demand down to the artificially low level of supplies in goods.

This is the central bank conundrum. Their limited tools to tackle inflation are just interest rate rises and balance sheet reduction. The US Fed and our own RBA hope they can engineer a “soft landing” to curtail inflation by raising interest rates to dampen demand, while maintaining low unemployment, without tipping the economy into recession.

For the first time since 2006, the yield earlier this month on US 2-year Treasury bonds rose above that of US 10-year treasury bonds. This is referred to as an ‘inverted yield curve’ and this historically indicates a recession ahead.

The bond market is signaling that the US Fed will raise short-term interest rates quite aggressively but then need to stop and perhaps even cut rates again if the economy slows due to those rate hikes. The bond market is essentially worried the Fed won’t be able to walk that fine line between a “soft landing” and an interest rate induced recession.

We agree an inverted yield curve is a worrying development. It may be that the US goes into a technical recession in 2023 while Australia has a slowdown that’s cushioned by our ties with China, who will likely stimulate their own economy soon. However, there are two important qualifications. First, the yield curve must stay inverted for a decent period (at least six months) to be taken very seriously. Second, an inverted yield curve predicts a recession within 6 – 24 months and 24 months is a long time not to be invested, especially if markets stay buoyant for longer. So, we’re watching with keen interest, but it may be premature for too much concern.

So, what’s an investor do?

As you can see, fixed interest investing is complex. It’s a key reason we diversify our fixed interest investments to balance across different maturities on the yield curve and across different kinds of fixed interest (government bonds, credit, real return strategies).

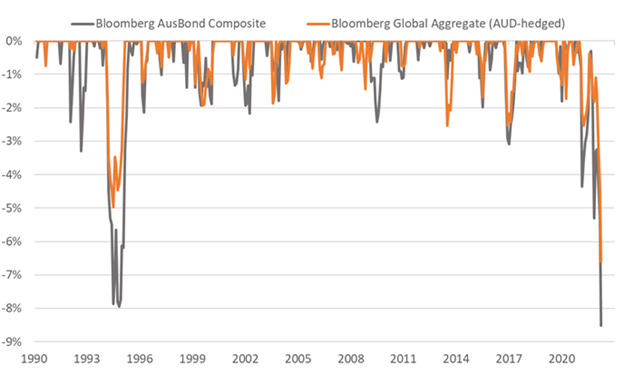

Investors in bonds have experienced some relatively significant short-term ‘paper’ losses. The chart below shows that bonds, as measured by the AusBond Composite and the Global Aggregate index, have recorded their largest peak-to-trough declines since the early 90’s.

Source: Betashares, Bloomberg: as at 22-March-2022.

With the wisdom of perfect foresight, an investor might have moved all their fixed interest investments to cash at the perfect time to avoid any drawdown while interest rate expectations were being priced into those investments. However, in the real world with central bank interest rates falling over the last 10 years and prolonged cash rates near zero, we aim to invest optimally by focusing on long term quality rather than try to ’time’ the market.

As is often the case in investing, it’s generally best not to sell investments after the loss. Now, with interest rate rise expectations now priced in to fixed interest markets, income yields on those investments are higher from today. That’s good news for fixed income investors. While capital values could continue to be volatile, we’re now earning good income from holding these investments as we look forward.

We continue to monitor the inverted yield curve while considering broader market implications and equity valuations. It may well indicate we’re heading for an economic slowdown but when and what impact it might have on the market is still too early to say. Meanwhile, our focus remains on high quality assets and companies that are likely to prosper in the long run. Diversification is critical and we maintain good exposure to real assets, including property, infrastructure, and commodities.